A single question drives our research: How has Earth remained persistently inhabited through most of its dynamic history, and how do those varying states of inhabitation manifest in the atmosphere?

Simply put, we are unraveling the evolving redox state of Earth’s early atmosphere as a guide for exoplanet exploration. Atmospheric redox and the abundance of associated gases are fingerprints of the complex interplay of processes on and within a host planet that point both to the presence and possibility of life. Redox-sensitive greenhouse gases, for example, can expand the habitable zone well beyond what is predicted from the size of a planet’s star and its distance from that energy source alone. Conversely, the absence of obvious biosignature gases such as oxygen does not necessarily mean a planet is sterile: cyanobacteria were producing oxygen on Earth long before it accumulated to remotely detectable concentrations in the atmosphere.

To organize our comprehensive deconstruction of the geologic record, from the earliest biological production of oxygen to its permanent accumulation in large amounts almost three billion years later, we selected four critical time intervals centered on a compelling question or controversy. These four so-called “Alternative Earths” represent highly varying states of habitability on our home planet that we can look for on distant worlds. Anchoring our first wave of research results are the fruits of extensive lab and fieldwork as well as first steps toward our ultimate goal of modeling early Earth atmospheres, beginning with the mid-Proterozoic. Indeed, our latest modeling of biosignature gases in the mid-Proterozoic atmosphere is revealing intriguing implications for climate stability and ‘false negatives’ in remote life detection—despite the earliest emergence of complex life in the oceans below. No matter what time slice of Earth history we tackle, our vertically integrated approach spans from a comprehensive deconstruction of the geologic record to a carefully coordinated sequence of modeling efforts to assess our own planet’s relevance to exoplanet exploration:

2016

-

Composition of the oceans and atmosphere: proxy development

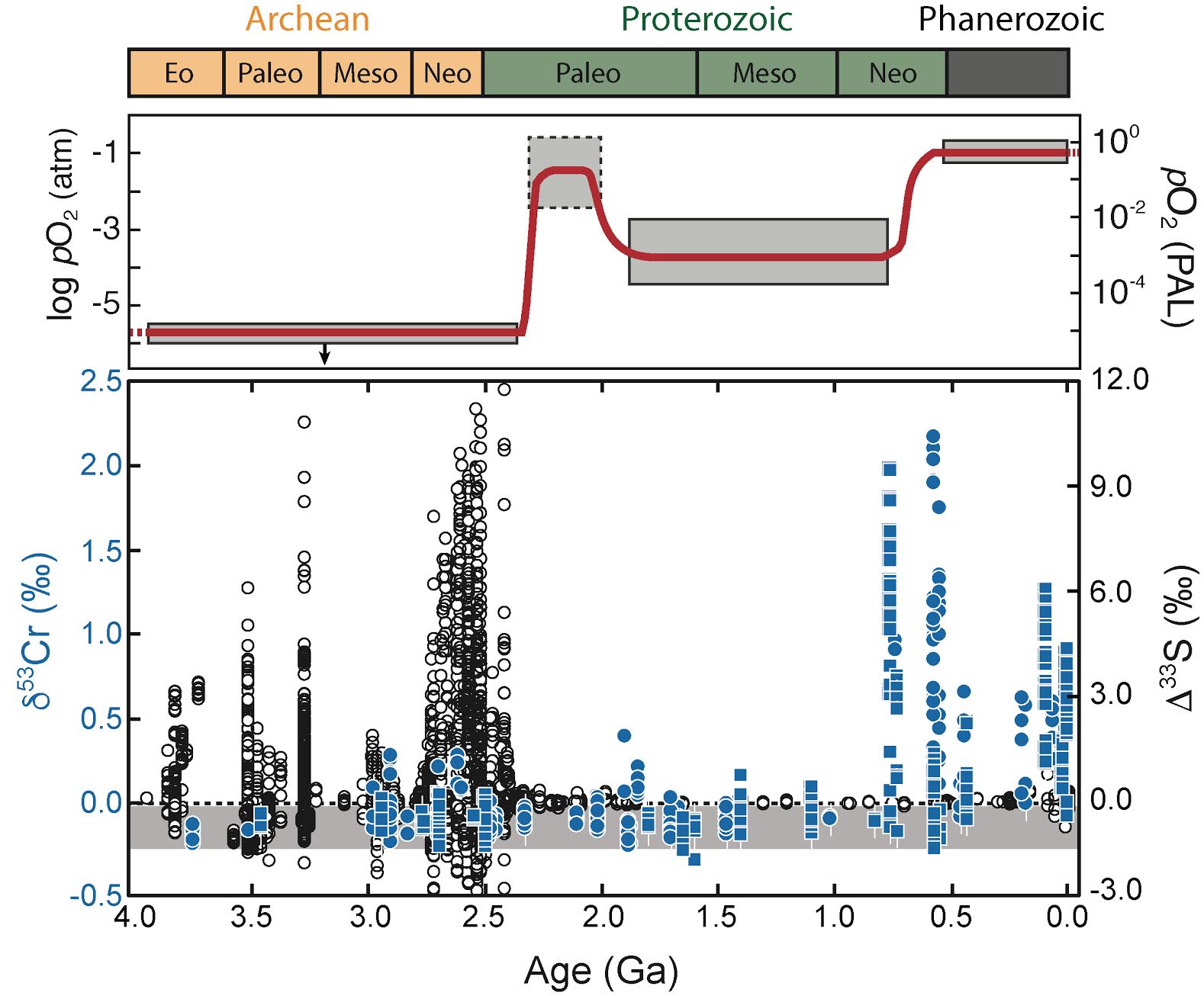

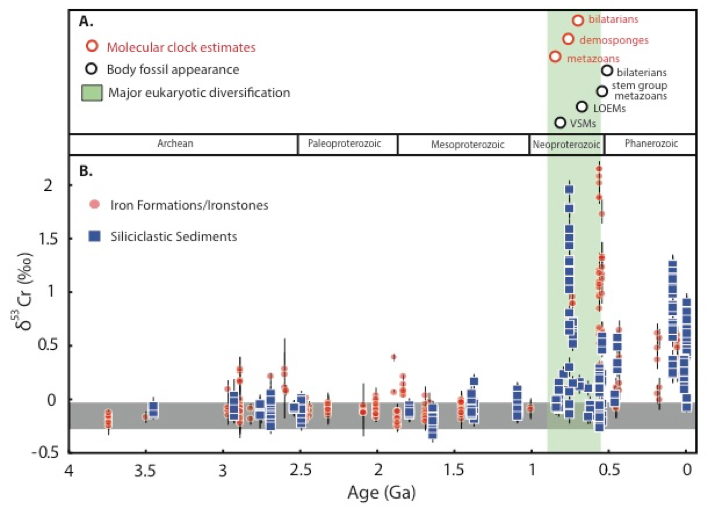

Building on the core strength of our team, the highlight is the most complete record to date of very low oxygen—and its direct impact on the biosphere—during the mid-Proterozoic. Work led by graduate student Devon Cole (Yale) and Noah Planavsky (Yale), working together with team members at GT and UCR, has produced a new and transformative chromium isotope record through Earth’s early history (Cole et al., 2016). Comprising more than 300 new chromium isotope measurements from 20 rock formations around the world, this work suggests that prior to 800 million years ago, atmospheric O2 levels were <1% of present atmospheric level (PAL)—contrasting sharply with previous estimates of O2 concentrations as high as 40% PAL. If correct, oxygen was clearly low enough to have directly hindered the diversification of complex life (see Gas Fluxes and Ecological Impacts: 3D Earth System Models).

To refine estimates of the atmospheric oxygen levels required to induce oxidative Cr cycling and explain the sedimentary chromium isotope record, we have initiated experimental Cr-Mn oxidation studies in the lab. We also continue to calibrate the utility of the chromium isotope and other proxies through studies of modern systems (Hood et al., 2016), analyses of metamorphosed, weathered, and hydrothermally altered rocks (Gueguen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016), and careful comment on the work of others (Planavsky et al. 2016).

To constrain oxygen levels in the all-important surface ocean, UCR graduate student Dalton Hardisty and PI Tim Lyons led development and application of the iodine proxy for reconstructing oxygen levels in the surface ocean. Application of this technique to a large suite of carbonate samples spanning Earth’s history suggests significant spatiotemporal variability of mostly low surface ocean oxygen levels for much of Precambrian time, including frequent upward mixing of O2-poor deep waters during the mid-Proterozoic (Hardisty et al., 2017).

OXYGEN IN THE ATMOSPHERE (figure above): Atmospheric O2 on Earth through time (upper) and select geochemical proxies for atmospheric pO2 (lower). In the upper panel, shaded boxes show approximate ranges based on geochemical proxy reconstructions, while the red curve shows one possible trajectory through time. In the lower panel, open circles show the magnitude of non-massdependent sulfur isotope (NMD-S) anomalies, shown as Δ33S. Filled blue symbols show chromium (Cr) isotope fractionations from iron-rich and siliciclastic marine sedimentary rocks throughout Earth’s history (Cole et al., 2016). Credit: From Reinhard et al., 2017

-

Gas fluxes and ecological impacts: 3D Earth system models

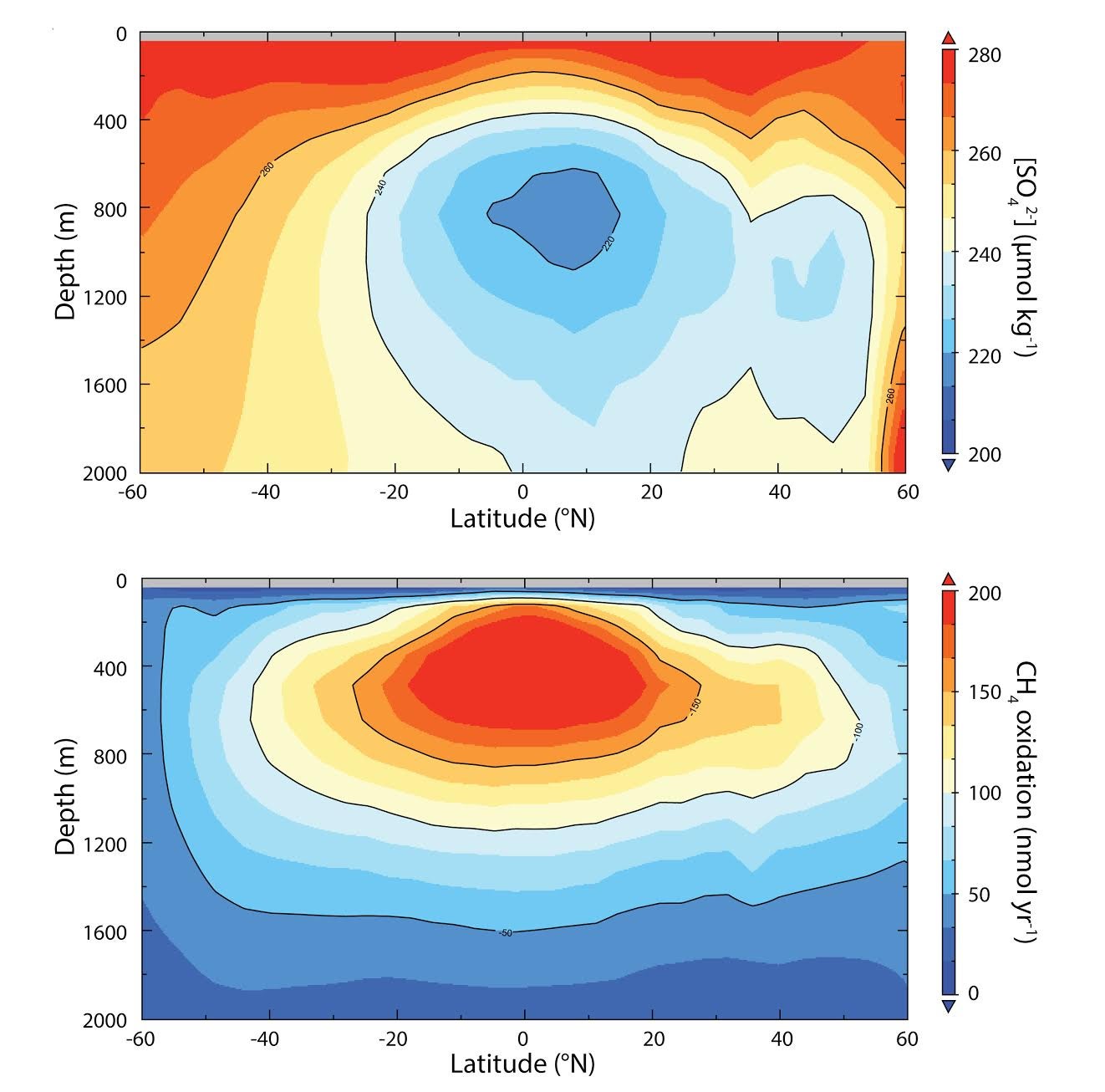

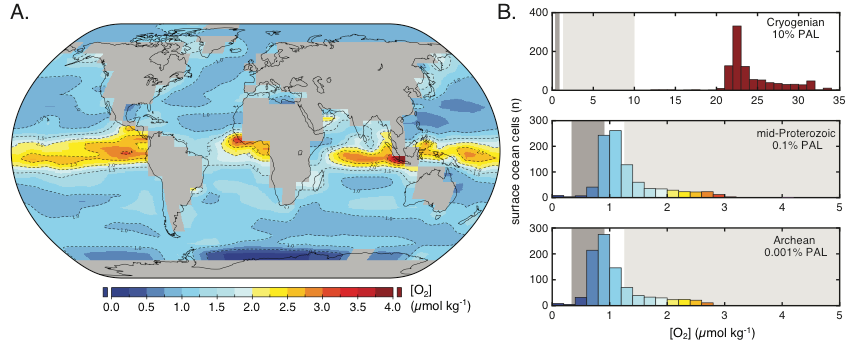

Understanding of the ultimate mechanistic underpinnings and ecological consequences of very low pO2 during the mid-Proterozoic remains a research focus for much of our team. Work led by graduate student Stephanie Olson (UCR), together with Tim Lyons (UCR) and Chris Reinhard (GT), has focused on the development of 3-D Earth system models designed to interrogate ocean-atmosphere chemistry on a mostly reducing planet. In particular, we incorporated parameterized O2-O3-CH4 photochemistry and an explicit representation of a consortial microbial metabolism that oxidizes CH4 anaerobically with dissolved sulfate, the latter being a consequence of the low but persistent oxygen levels in the biosphere. Results of this new model suggest that CH4 would have been an ineffective climate stabilizer even on an Earth surface that was only weakly oxidizing with mostly anoxic oceans. Astrobiologists now face a serious challenge to explain our planet’s early habitability—and the implications for other planets and their habitable zones are obvious. Identifying early Earth’s precise greenhouse cocktail, probably including water vapor, nitrous oxide, carbon dioxide, and only trace methane, is essential for spectroscopic efforts to assess the habitability of other planets in our galaxy (Olson et al. 2016a).

We have explored the potential consequences of low atmospheric pO2 on the ecological landscape faced by early eukaryotic and metazoan life (Reinhard et al., 2016). Results for Earth system modeling and simple dynamic models of local surface ocean O2 levels indicate a ‘patchy’ oxygen environment for much of mid- and late-Proterozoic time, even at pO2 levels well above those reconstructed with the chromium isotope proxy. These oases—local-to-regional settings dynamic on biologically relevant timescales—may have been inhospitable environments for the origin of animal life but could also have catalyzed evolutionary innovation through their intrinsic insolation and instability once certain ecological conditions were met. Even well-ventilated, shallow-water oases near the coasts, evidenced by iodine proxy (see Composition of the Oceans and Atmosphere: Proxy Development), would have been seasonally choked by anoxia and likely toxic, sulfide-rich waters rising up from the deep. These results are now a centerpiece in the team’s growing body of evidence that low oxygen in the ocean and atmosphere may have challenged the rise of complex life for hundreds of millions of years and detectability of that biosphere from remote locations.

METHANE MUTED (figure above): The numerical model use in this study, which calculated sulfate concentrations (top), methane oxidation (bottom), and an array of other biogeochemical cycles for nearly 15,000 three-dimensional regions of the ocean, is by far the highest resolution biogeochemical model ever applied to the ancient Earth. Previous models used no more than five regions. Credit: From Olson et al., 2016b

-

Stability and remote detectability of biosignature gases: 1D photochemical and radiative transfer models

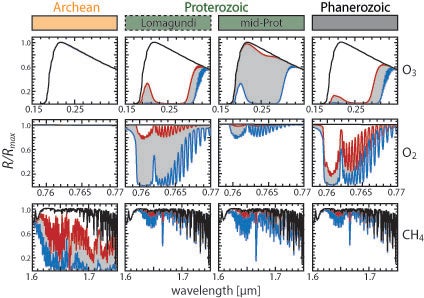

Recent developments from our geochemical proxy records and Earth system models provide insight into the long-term evolution of the most readily detectable potential biosignature gases on Earth—oxygen (O2), ozone (O3), and methane (CH4). In that light, we revisited evolving atmospheric chemistry on Earth in the context of the spectroscopic detectability of Earth’s biosphere (Reinhard et al., 2017). We suggest that the O2-CH4 disequilibrium biosignature, a gold standard in the exoplanet community, would have been challenging to detect remotely during Earth’s ~4.5-billion-year history and, remarkably, that atmospheric O2/O3 levels have been a poor proxy for the presence of Earth’s biosphere for all but the last ~500 million years. What is more, detecting atmospheric CH4 would have been problematic for most of the last ~2.5 billion years. Indeed, vast periods of Earth’s history would have appeared sterile by these traditional measurers, despite a thriving surface biosphere—representing a series of ‘false negative’ scenarios for remote life detection.

We stress that internal oceanic recycling of biosignature gases will often render surface biospheres on ocean-bearing silicate worlds cryptic, with the implication that the planets most conducive to the development and maintenance of a pervasive biosphere will often be challenging to characterize via conventional atmospheric biosignatures. This is our call to arms: future work must seek to identify novel biosignatures that are less prone to being overprinted by exchange with a liquid ocean, and this challenge is motivating our current research. More generally, we have demonstrated Earth’s indispensable, quantitative value in guiding the search for life beyond our solar system.

SYNTHETIC SPECTRA OF ALTERNATIVE EARTH ATMOSPHERES THROUGH TIME (figure above): Reflectance spectra of selected O2, O3, and CH4 bands for each geologic eon. Lower abundance limits are given in red, upper limits are given in blue, and the region between these limits is shaded grey. The black line represents the case with no absorption by O2, O3, or CH4. Credit: From Reinhard et al., 2017

2015

-

Tracing the fabric of oxygenation using chromium isotopes

A chromium (Cr) isotope record of evolving Earth surface redox. One redox proxy in particular has great utility in addressing atmospheric oxygen levels spanning all four Alternative Earth time intervals. The chromium (Cr) isotope proxy tracks periods when atmospheric oxygen was sufficiently high to support coupled oxidative cycles for manganese (Mn) and Cr in ancient soils. The critical benefit is that this tracer is sensitive to pO2 levels a few orders of magnitude higher than those required to turn off the preservation of non-mass-dependent sulfur isotope fractionation. As such, Cr isotopes can fingerprint levels of intermediate oxygenation that might manifest during transient ‘whiffs of oxygen’ in the otherwise oxygen-free Archean, for instance. Our results also show that Cr isotopes are particularly useful for tracing the fabric of oxygenation during the rise of eukaryotes following the Great Oxidation Event.

This work comprises more than 300 new Cr isotope measurements from 20 different geologic formations and shows a first-order shift in oxidative cycling of Cr around 800 million years ago. Although we are working to refine the precise oxygen levels needed to induce oxidative Cr cycling in typical continental environments (see Project Report for Alternative Earth 1), these data indicate that prior to 800 million years ago, atmospheric pO2 may have been < 1% of the present atmospheric level (PAL), which is close to theoretical estimates for the minimum oxygen needs of the earliest metazoans (see Figure 1). If correct, this is strong evidence that environmental oxygen levels were low enough to have directly impacted the diversification of complex life, a premise that a number of researchers have challenged in the last few years. In fact, it is possible that oxygen levels were lower for periods of the Proterozoic than they were during transient oxygen highs in the Archean. If correct, this conclusion marks one of the most fundamental shifts in our view of Earth’s oxygenation in decades—and provides strong impetus to continue our reassessment of basic aspects of Earth’s oxygen cycle and its relationship with co-evolving life and atmospheric compositions.

The chromium isotope proxy is the heart of our developing framework for very low atmospheric oxygen levels in the mid-Proterozoic; other independent proxies are indicating low oxygen in the shallow ocean and deep ocean as well (see Project Report for Alternative Earth 3). The importance of a full understanding of this pervasive oxygen stasis is difficult to overstate. The evolution of O2 levels in the mid-Proterozoic ocean-atmosphere system forms the backdrop for the initial emergence and subsequent evolutionary stasis of eukaryotic life—as recorded in the paleontological and organic geochemical records. Furthermore, the Cr data provide the possibility of a remarkably long period of Earth’s history during which many of the links among tectonics, climate, and life may have been short-circuited and/or amplified in unusual ways. For example, very low pO2 during mid-Proterozoic time likely limited O2 to “oxygen oases” within the Proterozoic ocean, and preliminary results suggest these oases—dynamic environments on biologically relevant timescales—were probably inhospitable for the origin of animal life despite recent suggestions for their low initial oxygen needs. If we are correct, this is a major conclusion that may explain the absence of animals during the mid-Proterozoic and the generally staid progress among all complex life.

-

Modeling the detectability of Earth’s mid-Proterozoic biosphere

Earth system model results for dissolved O2 levels in the surface ocean. Inhospitable is a relative term, of course. No matter how stifling the mid-Proterozoic environment may have been compared to the modern Earth, it was still unequivocally inhabited. If an exo-world were similarly inhabited, we would like to know how to detect it. So, did that Earthly inhabitation produce a clear signal? Our modeling of biosignature gases during this time interval is revealing critical implications. In particular, recent isotopic constraints on evolving atmospheric pO2 and oceanic SO42- suggest the possibility that a range of conventional biosignature gases (O2, O3, CH4, N2O) would have been difficult to detect spectroscopically for much of mid-Proterozoic time, despite the great abundance of at least prokaryotic life in the ocean at that time (see Figure 2). These efforts highlight the importance of long-term chemical disequilibrium between the surface ocean and the atmosphere. This disequilibrium allows for the recycling of biosignature gases within the marine environment without detectable expression in the atmosphere.

In short, a critical implication of our mid-Proterozoic atmospheric modeling effort is that extended intervals of Earth history might have appeared sterile through the filter of sea-air exchange—assuming searches that rely on the current suite of proposed biosignature gases for remote life detection and currently available and planned telescope technologies. Our ongoing work seeks to identify novel biosignatures that are less likely to be muted by exchange with a liquid ocean, with the aspiration that these results will inform the design of future telescopes intended for exoplanetary life detection.

-

Fostering interdisciplinary collaboration

We think of Earth’s atmosphere as the remotely detectable sum product of all the controlling factors on and within Earth that at any given time combine to sustain life. Those evolving compositions also capture evidence of great challenges to life—as during global-scale glaciations, major impact events, or severe nutrient limitation—and of life-sustaining tectonic processes. The primary objectives of our four Alternative Earths projects define a template for a broadly relevant and novel view of evolving redox and life on Earth, with the net expectation of resolving emergent atmospheric compositions that would bear the collective signature of the coupled tectonic and biogeochemical processes that produced them. To this end, our research strategy is carried out within four working groups, each broadly integrated in the range of expertise represented—with each informing, and being informed by, the others’ efforts.

Quite simply, we have been aiming since the inception of our proposal for an unusually, if not uniquely, unified effort that would not be possible outside the team structure of the NAI. Indeed, the whole already seems much greater than the sum of the parts. Our work on biotic versus abiotic cycling of N2O illustrates our team’s reliance on interdisciplinarity. In the lab, we are constraining the kinetics of N2O production in reducing abiotic systems, and then we leverage these experimental data in the context of atmospheric modeling—bringing together expertise at GT, UCR, and NASA's Virtual Planetary Laboratory. The results of this work are already yielding important constraints on evolving climate system stability and the emergence and maintenance of remotely detectable atmospheric biosignatures during early periods of Earth's history (see Project Report for Alternative Earth 2).

Our ongoing work on zinc (Zn) isotopes is another example of a truly interdisciplinary project that is only possible within a large collaborative network like our Alternative Earths Working Groups. Specifically, we are using Zn isotopes to track the rise of eukaryotes to ecological dominance and, at the same time, bridging those data with novel proteomics and quantitative modeling. In doing so, we have generated a new Zn isotope record that demonstrates that eukaryotes—although evolving before 1700 million years ago—only become important primary producers around 800 million years ago. These data provide a new view of cause-and-effect relationship between the diversification of complex life and evolution of Earth’s atmospheric composition (see Project Report for Alternative Earth 3).

Our Alternative Earths Team aims for a unified effort that would not be possible outside the structure of the NAI. Through collaboration among team members at GT, OHSU, Yale, and UCR, for example, we are studying the biogeochemistry of enzymatic manganese oxide formation and fractionation of stable isotopes under varying environmental conditions. Indeed, we brought together Yuanzhi Tang (GT) and Brad Tebo (OHSU) for this specific purpose. They had never met or collaborated before our Alternative Earths Team Kick-Off Meeting in April 2015 but have hit the ground sprinting since, including student exchanges and pursuit of independent funding for related projects (see Project Report for Alternative Earth 3).

Our team is also capitalizing on obvious synergism with the Origins of Complexity Team and the Virtual Planetary Laboratory (VPL). We have forged direct funded links to Origins of Complexity team member Greg Fournier (MIT) and to VPL team member Eddie Schwieterman through their 2015 NAI Director’s Discretionary Funding projects. Schwieterman’s plan is to couple our growing, comprehensive library of proxy-constrained estimates of ocean-atmosphere chemistry from the Proterozoic with the photochemistry/climate and radiative transfer models of the VPL. The ultimate goals are the integrated tools necessary to extend these diverse biogeochemical states toward a more complete understanding of a universe of possible exobiospheres. Fournier will study the rates and patterns of the acquisition and loss of genes coding for oxygen-associated enzymes in diverse microbial groups against a backdrop of changing biospheric oxygen as constrained by our team. The resulting insights into oxygenation dynamics during the Proterozoic should feed directly into our atmospheric modeling.

Collaboration between the Alternative Earths and Origins of Complexity NAI teams is bolstered by having members of both groups in the same department (Geology and Geophysics) at Yale. We have taken advantage of this opportunity by initiating several research efforts focused mainly on determining complex life’s role in shaping biogeochemical cycles and atmospheric evolution. (Indeed, we added a fourth Alternative Earth to our research repertoire based on our recent efforts and related ties to the Origins of Complexity (MIT) Team; our original proposal included only three Alternative Earths.) The productivity of this inter-team collaboration is already clear. Featuring authors from both teams, we recently published a paper in Nature Geoscience addressing how animals shaped the global sulfur and oxygen cycles—as well as an extensive review paper center on the interval leading up to the Snowball Earth glacial events. Furthermore, representatives from each team co-authored an article strengthening the case for early animal (sponge) biomarkers (see Project Report for Alternative Earth 4). In sum, we fully embrace the idea of inter-NAI team collaboration. We look forward to strengthening these ties as we move into Year 2 and beyond.